You should always expect to get a phishing message. Or at least that’s what we tell people. That is the solution to all our phishing problems, right?

Actually, I think this has turned out to be another one of those myths that we tell ourselves in the cybersecurity world. And to protect our communities effectively, we need to prove or disprove whether those myths are true or not. We need…are Cybersecurity Mythbusters!

For cybersecurity awareness month this year, I decided to hold a phishing tournament. I called it The Biggest Phisher. The rules were similar to a biggest loser competition: you got a point for not clicking a phishing message and you got an additional point by reporting those messages. And you lost a point by clicking. Winning the tourney would net you an extra vacation day, and we got almost 100 people to sign up.

I didn’t set out to prove or disprove this particular phishing myth, but I quickly realized that The Biggest Phisher created an environment where all of my contestants should have been expecting to get a phish. The contestants were highly engaged in the project…so much so they didn’t just report the simulated phishing messages they received, they also reported real ones.

We knew what our regular click through rates were for the University, and drumroll…the overall result of the contest was almost exactly the same as our other simulated phishing campaigns. Effectively, this means that even if people were expecting to get a phishing message, and they had a vacation day on the line if they did…they still only did about the same as everyone else.

Myth – busted.

Another surprise – for all the discussion we have about clicking vs not clicking, neither of these actions were all that common. By far the most common behavior was to do nothing. Almost 2/3rds of the participants in the biggest phisher ignored the phishing messages altogether. Some of these were because the phishing message copied other normal business emails, and the users really were desensitized to those messages. Others were too generic and participants ignored them because those messages just didn’t apply and they were too busy to think about them.

This made me rethink the way I look at phishing training.

If you were going to craft a phishing message, you want to send a message that is effective, but also you don’t want to set off alarm bells. If you have too many red flags, it will get reported and your messages will get blocked. But if even in the best case you know that 2/3rds of your email will just get ignored, you’ve actually got a very small window to aim for with your phish.

To keep the underwater phishing metaphor going…I call this target window, The Phishy Trench.

My goal as a defender probably won’t ever be to get people to ignore more of their email. And we do see a lot of our users already reporting phishing messages, but reporting phishing messages can be one area that to focus on to help improve your security outcomes. Phishing messages will make it past your filters. And we know that if a user is going to click, they’ll do it within the first hour after getting a phishing message. So the faster reports of a phish come in, the faster we can respond.

Myth #2 – Phishing is worse in the afternoons.

When I’ve talked to my peer CISOs in the community, nobody knew for sure what time of day phishing was most likely to come in. But there was a strong suspicion that cybercriminals were more likely to target people later in the day when they’re tired and just about to go home for the day.

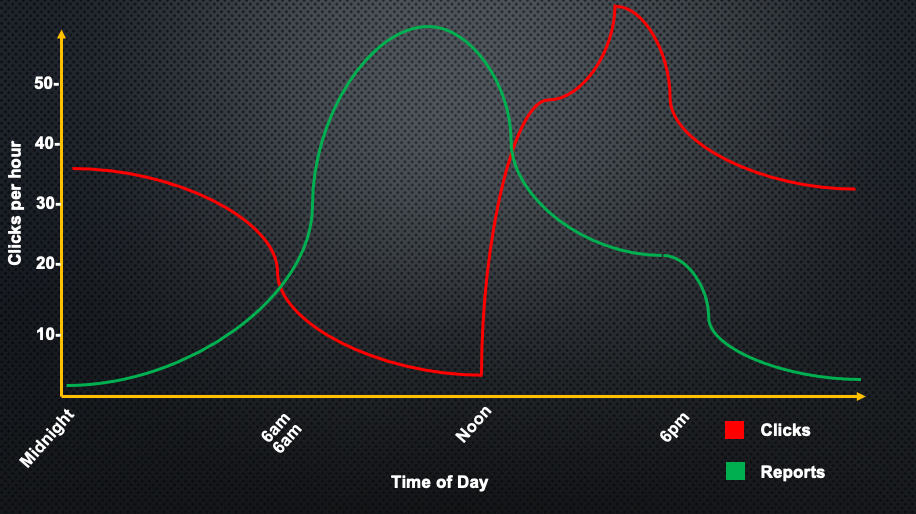

I’ve sent about 25,000 simulated phishing messages over the last 6 years. I plotted these campaigns based on what time of day that they were received. The result was that users were 8-10 times more likely to click on a phishing message in the afternoons over the morning. We also looked at real phishing messages that were received and reported by our users. We found that users were 3 times more likely to report a phishing message in the morning rather than the afternoon.

The explanation for this comes from neuroscience. It’s not as simple as users being tired or distracted. The real determining factor – circadian rhythms. Research suggests that humans are better at tasks that require good analytical or problem-solving skills in the mornings rather than the afternoon. These studies looked at doctors, soldiers, and students – and all of them made significantly higher mistakes when performing the same tasks in the morning, rather than the afternoon.

Myth – Confirmed.

Myth #3 – Users are dumb and don’t get our training.

One of the most common complaints today about security awareness training is that it doesn’t work. Security Awareness detractors frequently cite how users keep clicking on phishing messages, so therefore, the training doesn’t work.

Using the time of day data for phishing I mentioned above, there is another explanation for this phenomena. The data shows that my users were able to successfully identifiy phishing messages quite well during the morning. If users are 8-10 times more vulnerable biologically in the afternoons, then we should develop

Myth – Busted.

One of the techniques I’ve developed to help protect my users during the afternoon is called, Slow down and Frown.

You’ve probably heard the advice that smiling for 30 seconds can trick your brain into releasing endorphins and in turn, will make you happy. It turns out the same research also studied frowning, and suggested that it could make you more vigilant for threats in your environment.

I didn’t have a good way to test this theory on phishing until I started planning the Biggest Phisher competition. At the beginning of the competition, I split the contestants into a control group and a frowning group. I trained the latter group to frown while reading their email. At the end of the tournament, the frowners were 43% less likely to have clicked on a phishing message than their non-frowning counterparts. But there was another unexpected benefit…the frowners were also nearly 3 times more likely to report the phishing messages.